Let us walk through this door in the Turin Museum and not only look around at the objects on display

but also look over our shoulder and look back across time, across centuries.

Entrance to the permanent exhibition of the objects from the tomb of Kha in the Turin Museum

In the season of 1906 Ernesto Schiaparelli and his 250 workers had been working for four weeks at the

site of Deir el-Medina with little results to show for their relentless shift work until they came across a

tomb. They were working at the top of the western cemetery in the area of the decorated chapel,

surmounted by a small pyramid, already discovered by Bernardino Drovetti in the early years of the 19th

century. The name Kha was known from the walls of that chapel and strangely enough Kha’s funerary

stele (below right) had made its way to the Turin collection decades before Schiaparelli’s work at the

site. Kha’s tomb’s burial chambers escaped discovery because they had not been located beneath the

tomb chapel as is usual, but rather within the hill opposite.

If you are fascinated by mummies, pharaohs, and ancient civilizations, then you probably enjoy video games with these themes. Head over to this page and discover the best slots games that feature stories from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Apart from slots, you can also play other casino games like roulette and poker.

View of the slopes of Deir el-Medina’s western cemetery,

where the tomb of Kha is situated

Stele of Kha and Meryt

Painted limestone

Height: 77 cm

N.Cat. 1628 = N. 50007

From the Drovetti collection

When the flight of the steps near the hillside was discovered, Ernesto Schiaparelli was accompanied

by the Antiquities Service Inspector Arthur Weigall to discover where the passage leads.

“The mouth of the tomb was approached down a flight of steep,

rough steps, still half-choked with debris. At the bottom of this

the entrance of a passage running into the hillside was blocked by

a wall of rough stones. After photographing and removing this, we

found ourselves in a long, low tunnel, blocked by a second wall a

few yards ahead. Both these walls were intact, and we realized

that we were about to see what probably no living man had ever

seen before…”

Ernesto Schiaparelli’s bust, Turin Museum

The two walls were removed. Now the two excavators were standing in a roughly cut corridor of about

standing height. Lined up against the wall on the left were pieces of burial furniture, several baskets,

a couple of amphorae, a bed and a stool and a carrying-pole. At the far end of the corridor was a

simple wooden door.

“The wood retained the light colour of fresh deal, and looked for all

the world as though it had been set up but yesterday. A heavy

wooden lock held the door fast. A neat bronze handle on the side of

the door was connected by a spring to a wooden knob set in the

masonry door post; and this spring was carefully sealed with a small

dab of stamped clay. The whole contrivance seemed so modern that

professor Schiaparelli called to his servant for the key, who quite

seriously replied, “I don’t know where it is, sir”.”

With no key to open the door, the lock was carefully cut with a fret-saw to gain access to the

chamber beyond. When the door swung open for the first time in more than three thousand years,

the burial chamber was revealed.

The whole burial was orderly and carefully placed within the space. The principal items were still

covered with dust-sheets that were still strong to the touch. The floor was neatly swept by the last

to have left. A single papyrus-column lamp-stand made of wood supported a copper-alloy saucer still

containing the ashes produced by its ancient flame.

“One asked oneself in bewilderment whether the ashes here, seemingly not cold, had truly ceased to

glow at a time when Rome and Greece were undreamt of, when Assyria did not exist, and when the

Exodus of the Children of Israel was yet unaccomplished”.

The tomb and its contents reflected the owners’ personal wealth, their particular position within the

society and their life history. It suggests a picture of a prosperous, 18th dynasty home, packed

away in preparation for re-use in the af

terlife.

Low tables were piled with food offerings: vegetables, heavily seasoned minced greens ( Kha was

nearly toothless when he died), mashed carob, grapes, mumusops fruit and dates, salt, cumin, braids

of garlic and juniper berries

loaves of bread in a wide range of

shapes and sizes, salted meats

(including duck)

baskets for the storage of food

Amphorae, some elaborately decorated, contained fine wines,

grapes and flour

Two-handled pottery storage jar.

The body is painted with rishi

(feather) decoration, the

linen-covered neck with various

sacred emblems applied in brightly

coloured paint. A hieratic docket

records Kha’s name

The tomb belonged to Kha, a royal architect, and to his wife Meryt.

Kha was active during at least three and possibly four reigns – those

of Tuthmosis III (1504-1450 BC), Amenhotep II (1453-1419 BC),

Tuthmosis IV (1419-1386 BC) and Amenhotep III (1386-1349 BC),

pharaohs of the 18th dynasty.

It is not difficult to build up a picture of Kha as an individual – it

is demonstrated by the number of items inscribed with his name

or objects that belonged to him by virtue of his trade and rank

during his lifetime. We also have insight into his personal life

through his clothes, jewellery, furniture, toiletries and favourite

pastimes. Approximately 196 objects can be attributed to Kha.

Kha’s body was placed in a series of expensive coffins that he had created for himself. He had a

large black outer rectangular coffin rested in two anthropomorphic coffins in black and gold showing

fine craftsmanship. Kha’s mummy is better preserved than that of his wife. An X-ray analysis has

shown that Kha has a gold “necklace of val

our” around his neck under the many layers of tight

wrappings. This type of ornament was supposedly bestowed upon individuals by pharaoh himself. His

body is decorated with additional fine jewellery. He was buried with a wide collar made up of a

string of gold rings. A long necklace of spun and plaited gold supporting a heart scarab, a tyt amulet

probably of carnelian, a ururet amulet in the form of a snake’s head, probably also in carnelian, on

his forehead; a pair of gold earrings and a bracelet on each arm made of a strip of gold.

gilded anthropomorphic coffin of Kha

Gilded coffin depicts the

ibis-headed wind god whose role is

to restore the ability to breath to

the dead person’s nose

From Kha’s personal items we get sense of his

responsibilities, rank and pharaoh’s admiration for his

skills. His cubit rule is covered in gold leaf – it was a

personal gift from Amenhotep II as a recompense for the

rapid construction of a building. His scribal pallets and a

writing tablet are beyond the cubit rule on the right.

Smoothers or irons for papyrus

The tomb contained many pieces of furniture: apart from Kha’s and Meryt’s wodden beds complete

with wooden headrests and linen, there were several decorated and white painted storage chests

packed with clothing and other objects of daily use, brightly painted and inscribed chair, painted stool,

2 white wooden tables, small wood and ivory box and a single, folding, duck-headed stool.

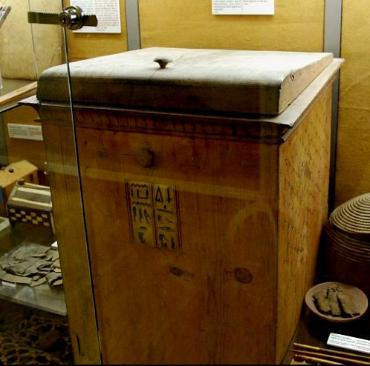

White painted box of Kha

Wooden stool

Two of the painted-wood linen chests from the burial of Kha and Meryt. The one on the left is

decorated with floral and geometric motifs, the one on the right is painted with naive scenes of the

deceased and his wife seated before a loaded offering table and attended by two of their children, and

poorly executed hieroglyphic inscription.

Fine tapestry work

Sandals made from vegetable

fibre. There were also leather

sandals belonging to Kha found

among the goods.

The only example

of a lightweight

linen tunic without

sleeves, for

summer.

The tomb contained 26 knee-length shirts and about 50 loincloths,

including short triangular pieces of material that would have been

worn in the context of agricultural or building work. 17 heavier

linen tunics were provided for winter wear, while 2 items described

as “tablecloths” were among Meryt’s clothes. Kha and his wife

each had their own individual laundrymarks, and it is known that

there were professional laundry men attached to Deir el-Medina.

Metal vessels belonging to Kha were of intrinsic value

Perfume container imported from

the Mycaenian colony in Cyprus.

Two blue faience rings belonging to Kha

Senet was the most popular board game known to the Egyptians. It was played

either on elaborate inlaid boards or simply on grids of squares scratched on the

surface of a stone. The two players each had an equal number of pieces, usually

seven, distinguished by shape or colour, and they played on a grid of thirty squares

known as perw (houses) and arranged in three rows of ten. Moves were determined

by throw-stics or astragals (knuckle-bones). The object was to convey the pieces

around a snaking track to the finish, via a number of specially marked squares

representing good or bad fortune.

Kha’s wooden gaming-board with a little drawer to hold the pieces was most likely

to have been used during his life.

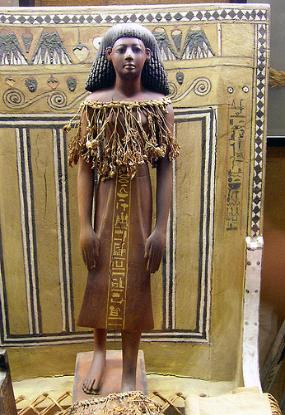

Funerary statuette of Kha, that

had been garlanded and placed upon

a brightly painted and inscribed

chair of Kha.

Wood

Height: 43 cm

Two shabtis of Kha were deposited in the burial chamber, one of whom, with agricultural tools, was

inside a model sarcophagus, quite similar to the external coffin where the body of the deceased

rested (Inv. Supl. 8337-8341). Meryt did not have funerary statuettes.

wooden shabti of Kha

stone shabti of Kha

Within Kha’s coffin was one of the earliest copies of the Book of the Dead on papyrus. It is 14

metres long and is illustrated with high quality coloured vignettes.

Section of the well preserved

funerary papyrus. The deceased

and his wife, hands in adoration,

are received into the presence of

Osiris, ruler of eternity,

enthroned beneathed a

flower-bedecked canopy. A heaped

offering table stands before them.

The mummy of Kha’s wife Meryt was contained in a rectangular outer shrine containing a singular inner

gilt anthropomorphic coffin and a mummy mask made of stuccoed linen and the striped wig was marked out

alternatively in blue paint and gold leaf. The face was gilded, eyebrows and eye sockets inlaid in blue

glass, and the eyes made of opaque white and translucent black glass. It is likely that she died before

h

er husband did, as her body was placed in a coffin originally constructed for Kha, and inscribed with his

name. It was a less expensive assemblage than the series of coffins Kha was buried in. There is no

evidence that Meryt died suddenly or prematurely, but it appears that afterlife preparations in Deir

el-Medina were concentrated around the lives of husbands, rather than their wives. The choices made at

the

point of burial were made by Meryt’s husband and possibly their sons, Nakht and Userhat. Her own

personal possessions (e.g. wig, toiletries, clothes and furniture) were included for her use in the

afterlife, but although some 196 objects could be attributed to Kha, only 39 could be attributed to

Meryt individually. 6 items were inscribed with names of both of them.

Meryt’s bed was found

made up with sheets,

fringed bed covers,

towels and a wooden

headrest encased in

two layers of cloth.

Meryt’s body was not prepared and wrapped as well as Kha’s. As a result her mummy is not as well

preserved. Neither body was embalmed. When Meryt’s mummy was x-rayed, it revealed a broad

collar made up of eight strings of hard-stone plaques, two pairs of gold earrings and a girdle hanging

low on her pelvis consisting of eleven gold plaques linked by five strings of glass or faience beads.

These plaques are in the form of bivalve shells, which were symbolic of female sexuality in ancient

Egypt. Meryt had considerably less jewellery than her husband and was made from less expensive

materials. Evidence from the Western Necropolis at Deir el-Medina reveals noticeable disparities in

the quantity and quality of goods provided for women throughout the 18th dynasty. This may reflect

something of the relative social status of men, women and children during life, not merely in death.

For the elite at Deir el-Medina, the tomb was very much a male sphere and constituted around a

man’s life on earth.

The dressing table of Meryt

Brightly painted wooden box

containing cosmetic vessels of

alabaster, wood, faience and glass.

Inside Meryt’s cosmetic and trinket

boxes were also her work-basket

with needles, 3 bronze razors, 3

wooden pins, 3 wooden combs. Larger

decorated chests were packed with

clothing.

The wig of Meryt was found

perfectly preserved in a wig box of

acacia wood. It is probably the

finest of her belongings.

Detail of the hieroglyphic inscription on

Meryt’s wig box

Take a closer look at another one of our similar content posts.

Sources :

1.Reeves, Nicholas: Ancient Egypt : the great discoveries : a year-by-year chronicle

London : Thames & Hudson, 2000.

2. Meskell, Lynn: Intimate archaeologies : the case of Kha and Merit. IN: World Archaeology, Vol.

29, No. 3, Intimate relationships (Feb. 1998), p. 363-379.

3. Shaw, Ian, Nicholson, Paul: British Museum dictionary of ancient Egypt

London: British Museum Press, 1995.

4. Borla, Mathilde : Les Statuettes Funéraires du Musée Égyptien de Turin In: Dossiers

d’Archeologie 2003

5. KMT, vol. 14, pt. 1